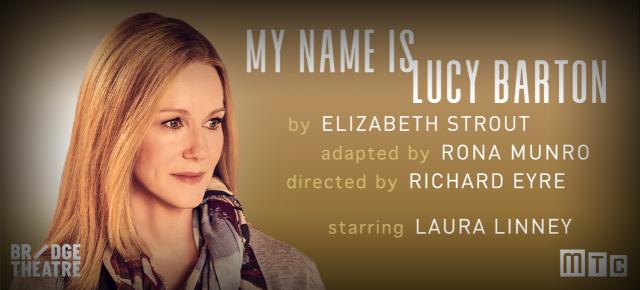

My Name is Lucy Barton written by Elizabeth Stout and published to a chorus of hosannas in 2016, is now a one-woman, two-character play, running through Saturday, February 29, 2020 at Manhattan Theater Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre on Broadway. Adapted from the book by Rona Munro and directed by Richard Eyre, Lucy Barton stars Laura Linney, an actress whose every outing (be it film, stage, or TV) seems to elicit a cascade of unanimous raves. Tellingly so, her Playbill bio lists countless nominations and acting awards. Linney’s last Broadway appearance was in 2017 in Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes where, alternating the roles of Regina and Birdie with Cynthia Nixon, Linney garnered her 4th Tony nomination. I’d like to say that My Name is Lucy Barton, which debuted in London in 2018 to rave reviews, blew me away. Alas, the entire 70-minute production, despite much talk about Lucy’s varied life experiences, proves listless to the point of boredom. It is not that the director (and I imagine Linney too) don’t try to breathe some life onto the stage by adding movement, as well using various location projections (Bob Crowley). But neither does much to quicken one’s mind or pulse. The biggest problem is the play, still essentially a piece of literature, better read than seen. And it’s far too intimate for such a large venue; it is all but lost in space. Nevertheless, Lucy’s story is sensitively told by Linney, mostly in quietly delivered decibels. But Lucy’s journey, predictable from the get-go, offers no excitement, no surprises, and almost no humor, that is, unless you buy into the gossipy small-town stories told in a midwestern bark by her visiting mother (also played by Linney). The play which covers Lucy’s journey from childhood, leaving home, marriage, two kids, a divorce, and remarriage, to becoming a writer of a bestselling book, does offer a few strands of beautifully written and heartfelt thoughts for the audience to think about (or wallow in) if that is their wont. Setting the scene, the play softly, almost apologetically, opens in an obvious hospital room with only a bed and a chair on view, with the casually dressed Lucy, coming downstage and informing the audience tentatively that “there was a time, and it was many years ago, when I had to stay in a hospital for almost nine weeks. . . . This is the memory I reach to, to begin this story. Perhaps that is because, in those nine weeks, I was, at times, uncertain of my survival.” As the story goes, Lucy went into the hospital to have her appendix taken out, and “after two days they gave me food, but I couldn’t keep it down. And a fever arrived. No one could isolate any bacteria, or figure out what was wrong. No-one ever did.” Lucy informs us at this time she had a husband William who rarely visited her—as he was busy running the household and busy with his job. Also, he hated hospitals, as his father died in one when he was fourteen. Lucy also talked about missing her two young daughters who were at home. Three weeks into her hospital stay and suffering from loneliness, Lucy wakes up, and, sitting at the foot of her bed is her mother, whom she hadn’t seen in years. Hearing her mother call her by her long-ago pet name Wizzle calms Lucy down, “It was as though all my tension had been a solid thing, and now it dissolved. That night for the first time I slept without waking.” Thus, begins the bulk of the play, around which most of the action, if you can call it that, occurs. During her stay, Lucy’s mother rarely leaves the set’s one chair. This is her perch for the entire play. Lucy, on the other hand (not that it adds much variety), does have some 15 feet of free reign. A certain sadness, one can call it a disconnect, exists between Lucy and her mother. No doubt they love each other in their own way, but there is too much baggage, and too many years to wade through, most of which remains silent, as neither ask the questions that would possibly pierce the protective wall surrounding them. The mother never asks about Lucy’s husband, and Lucy never questions her mother about her still-living father who fought in the second world war and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

We do learn that Lucy and her siblings were beaten and deprived of TV, films, and magazines, and that her father once locked Lucy in his truck. A lot of time is spent during the mother’s visit with each of them staring at each other, in wonder, if not disbelief. After five days the mother leaves as abruptly as she appeared. “I have no idea if she kissed me goodbye, but I cannot think that she would have. I have no memory of her even kissing me,” Lucy says. Amidst telling the story of her life, both then and now, Lucy does manage to ask her mother if she loves her. The answer, indicative of their guarded relationship: “when your eyes are closed.” As far as Lucy opening up to her mother, “I wrote my mother a letter. I said I loved her, and I thanked her for coming to see me in the hospital. I said I would never forget that.” The mother’s answer arrived on a postcard, signed “M.” Lucy notes, “I will never forget that either.” A resigned peace seems to have taken place on both sides.