Leo Ledger has an addictive gambling habit and a propensity for losing bets. This not-uncommon correlation stems from his conviction that he is unworthy of happiness, so that his efforts to conceal this flaw are orchestrated to ultimately reaffirm his failure. His wife wearied of this game long ago, leaving him with custody of their son Albert, who is now 19 and departing for college, after supplying his father with a semester's worth of latchkey instructions for the maintenance of the household. Will these measures prove successful?

Hard-drinking Margaret Whitney, by contrast, realized her error in choosing a mate almost immediately following the wedding. When her daughter was born, Margaret promptly divorced her unpromising spouse and proceeded to fabricate a history meant to ensure that her offspring would follow a less precarious path. Oh, but Lucy is now 19 and attends the same college as Albert, where they meet and take a fancy to one another. What could go wrong?

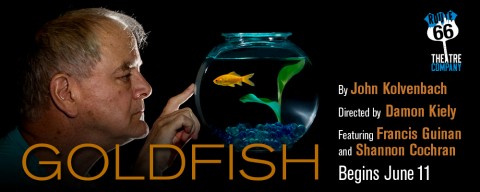

John Kolvenbach has always been fond of adults behaving like preteens, so it's no surprise that much of his Goldfish is devoted to Leo and Margaret parading their immaturity with, respectively, fumbling humility and flinty defiance. (The latter's practice of shrugging off contradictions in her testimony with a casual "so I lied," soon grows more annoying than endearing.)

To be sure, they are played in this Route 66 production by Frances Guinan and Shannon Cochran, both of whom have been portraying lovable variations on these personalities for most of their careers.

Sharing the dysfunctional-family tropes are Alex Stage and Tyler Meredith, whose shy Albert and forthright Lucy poignantly convey the curiously detached emotional impetuosity so often observed in adolescents long accustomed to disappointment.

As scenic designer Collette Pollard's museum-accurate working-class kitchen hides a labyrinth of wagons and drawers suggesting auxiliary locales, Damon Kiely's direction strives to camouflage the narrative gaps lurking beneath the script's veneer of everyday realism—the scarcity of textual clues to the passage of time, for example, or Kolvenbach's ambivalence on the question of whether children are predestined to repeat their parents' mistakes (although he appears to be resigned to its inevitability).

In a universe where impulse-driven youths are doomed to marry in haste and repent at leisure, however, a promise to wait a little longer before doing so and the freedom to pursue that plan represents an intergenerational compromise as close to a happy ending as we can desire.