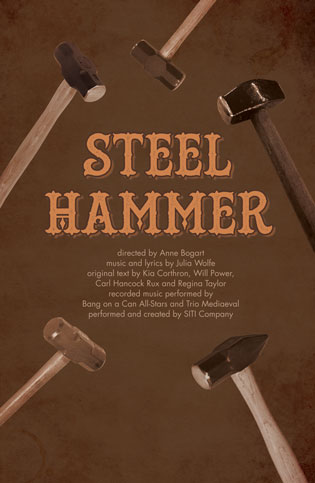

At two hours with no intermission, Steel Hammer, the avant-garde deconstruction of the traditional ballad "John Henry," is physically and emotionally demanding. The producing company, Saratoga International Theatre Company (SITI), was co-founded in 1992 by the Japanese master Tadashi Suzuki and Columbia University professor and director Anne Bogart. After the first five years, Suzuki ceased participation but the company continues to follow the Suzuki method which entails cult-like discipline and dedication.

One man enters and strikes a pose stretching and extending at an oblique angle. Soon he is joined by an ensemble that includes: Eric Berryman (John Henry) and Patrice Johnson Chevannes (Polly), who are guest artists for this production, then the regular company members Akiko Aizawa, Gian-Murry Gianino, Barney O'Hanlon and Stephen Duff Webber.

There are many cooks concocting the heady broth that is the multi-media drama Steel Hammer. The first of four, approximately half hour segments sees the cast moving through a series of sharply punctuated postures. With a more psychological edge, the poses and actions recall Tai Chi. They signify aspects of the legendary John Henry's story: manual labor, captivity, struggle and death.

Over the four sections many different aspects of movement and music are explored. There is the hauntingly minimalist score by Julia Wolfe which inspired the piece. A segment that is “acted” with text explores the back story of the legendary black convict on a work gang who died in a contest to beat a steam hammer. Elements of clog and step dancing are included as well as Berryman in a virtuoso demonstration of hambone, or hand jive that entails syncopated, rhythmic hand clapping and body slapping. Another sequence has the performers race around a circle to evoke the frenzied, physically exhausting contest between man and machine that ends in Henry’s death.

There is a wide vocabulary of movement. Some of the most riveting images come when the actors link arms or join to form a snaking mass. It feels like a more elemental aspect of the familiar acrobatics and contortions of Pilobolus Dance Company.

In addition to the score by Wolfe that stretches out the traditional folk song to album length, the production is inspired by recent historical research. Scott Reynolds Nelson's 2006 book, "Steel Drivin' Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend," states that John Henry was based on a real character: John William Henry, a New Jersey–born free black man who went to Reconstruction-Era Virginia. Following the disaster of Reconstruction, life in the South reverted back to what it had always been. Now liberated, destitute former slaves returned to plantations as share croppers. There was no essential improvement in the quality of their lives. Like many, John Henry was convicted of trumped up charges, given a long sentence, and pressed into a chain gang. Wardens of prisons routinely leased convict labor. It is likely that the historical John Henry worked hammering holes into granite for blasting of a tunnel constructed by the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) railroad. The production, which premiered in Louisville, evolved in a complex manner. Initially there was a dialogue between Humana Festival artistic director, Les Waters, and the composer. He suggested the renowned director Anne Bogart. They in turn enlisted the authors of the production's text — Kia Corthron, Will Power, Carl Hancock Rux and Regina Taylor. Including a Humana dramaturg, Steve Moulds, with the cast of actors, they developed the complex, multi-layered work. The resultant piece, while intriguing in its many elements, is demanding on the performers as well as the audience. Owing to slow and repetitive passages, the show’s running time of two hours taxes one’s patience and endurance. In dialogue with a senior critic who hated the piece, I suggested that the tedium might be a metaphor for the passion and suffering of John Henry. His response was that making the audience suffer does not make for great theater. It is also possible that responses to the work are divided between those with more traditional paradigms for theater and individuals willing to embrace new and expanded forms of expression. I wonder, for example, if the production would have a different reception at Jacob’s Pillow, with its mélange of dance/ movement. Or at BAM, the venue for avant-garde, multi-media productions by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. Though less sophisticated as dance, the piece reminds me of recent polemical theatrical works by Bill T. Jones. Text and story telling have become an ever-more-prominent aspect of his choreography. To see Steel Hammer in a proper context, one must be willing to accept that there is increasing cohesion and cross referencing among text, dance and music. That’s just as it was in ancient Greek theater and here, in the case of Tadashi Suzuki (born 1939), who drew on the Japanese traditions of Kabuki and Noh. That combined with aspects of martial arts movements conflates as the unique Susuki Method which is adhered to by Bogart’s SITI company. The Suzuki method of acting has been taught at schools such as Juilliard, Columbia and the Royal Shakespeare Company. It builds an actor’s awareness of the body, especially its center. The method uses exercises that are inspired by Greek theater and martial arts and require great amounts of energy and concentration. They result in the actor becoming more aware of natural expressiveness and allow commitment to the physical and emotional requirements of acting. Earlier in the week at Humana saw a special session on collaborations. A founding member of Bogart’s company fought back tears when discussing the degree of commitment and discipline required over many years. More than the usual theater company, it is a lifestyle of constant physical and emotional training. Because of the aspect of stamina and fitness, it is more like a dance than theatre company. And there are similar stresses and injuries. Following a matinee and preceding an evening performance we encountered Berryman in the lobby. While asking him about the endurance of a double header, I noticed a boot on one leg. He explained that his ankle had been sprained because of the demanding foot stomping and clog dancing. Did I notice that he had been shifting his weight and sparing that foot he asked? Not really was my response.

Perhaps if I saw the piece a second time, there would be more possibility to concentrate on its complex and diverse elements. There was some discussion that the piece is headed to New York. Given the chance, yes, indeed, I would see it again. Within the context of the generally mainstream Humana Festival, this was the only work that truly pushes the envelope and provides glimpses of where we are headed for theater in America. While I have mixed responses to the success of this work and its four part, Rashamon-like deconstruction of a traditional folksong, which is to say a bit of a stretch, overall I am grateful to Humana for providing the experience. It’s a potent reminder that critics have to keep pace with the innovative works of our time. We owe that to the artists, and more importantly, audiences. That can be both challenging and exhilarating. /p>