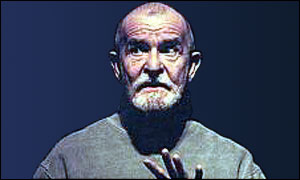

Athol Fugard has been called "the conscience of South Africa." But he would rather refer to himself as "a harmless old liberal fossil." Regardless of which is truer, Fugard's art has been so passionately motivated by the history and the turbulence of South Africa under apartheid, one has to wonder what new pockets of unrest and social turmoil will next inspire the internationally renowned, 69-year-old playwright. While theatres around the world continue to produce the most popular works in the Fugard canon, including Blood Knot, A Lesson in Aloes, Master Harold...and the boys, The Road to Mecca and My Children! My Africa, and eagerly await each new play, it is New Jersey's McCarter Theater that has served as a welcoming "home" to Fugard since 1994 (the year apartheid was abolished) when he came here to direct an early work, Hello and Goodbye.

Fugard has deepened his relationship with the McCarter and in particular with Emily Mann, its artistic director, who has been notably receptive to nurturing and producing his more recent plays, including the lyrical Valley Song (1995), the biographical The Captain's Tiger (1998), and currently the world premiere of Sorrows and Rejoicings, running May 1-20. Following the McCarter engagement, Fugard will direct the play with a different cast in Capetown, South Africa. After that, the play will cross the Atlantic once more for its New York City premiere at Off-Broadway's Second Stage, in a separate mounting from the McCarter production.

"Nothing tests a new play more than that first rehearsal period. That is when you either know you've got something that works or know it doesn't," says Fugard candidly at the start of our phone conversation following an early rehearsal. And unless he was just revving himself up for our chat, he gave every indication, particularly by the way words just started tumbling out, that he was exhilarated by the rehearsal.

He was, after all, surrounded by his extended family. Fugard continues a 20-year collaboration with the play's co-director Susan Hilferty (who is also serving as set and costume designer). This production also marks Fugard's 15th year collaborating with lighting designer Dennis Parichy.

Fugard is anxious to give credit to his cast for opening the play up. Besides Tony Award-winner L. Scott Caldwell (Joe Turner's Come and Gone), the production reunites two other Tony Award-winners Blair Brown (for Copenhagen) and John Glover (for Love! Valour! Compassion) who first worked together 20 years ago in the American premiere of David Hare's Plenty. Fugard is particularly enthusiastic about the play's other cast member, South Orange, New Jersey-born and raised Marcy Harriell (who played Mimi in Rent on Broadway), a 1990 graduate of Columbia High School.

"Look at that cast we have. I now believe it is going to work on stage," says the playwright who should, at this point in his career, have little doubt that his plays can be counted on to not only reflect his country's changing history but also to reveal his own continuing artistic growth. Fugard has set the play in the semi-desert Karoo region of southern Africa, his beloved birthplace. In Sorrows and Rejoicings, an important character, David Olivier (pronounced Dahvid Olifeer in Afrikaan), a political activist writer and poet, is dead when the play begins. Compelled to leave South Africa and the black woman he loves, David had gone into exile when his articles were banned and he was threatened with jail. When his self-imposed sojourn in England did not give him the freedom he sought, his life and his life's work began to disintegrate. At his death eighteen years later, his body is returned home for burial. The play focuses on the uneasy meeting at David's family home of Allison (Brown), David's white British wife and Marta (Caldwell), the black woman who was his lover and the family servant. Also present at the family home is Rebecca (Harriell), David and Marta's bitter and estranged eighteen-year-old daughter, as well as David's returning spirit.

I asked Fugard whether there were any parallels between what happened to him and the events in the play, or did he draw more upon what he saw happening to others? "During those early tumultuous years when the Afrikaner (a South African of Dutch descent) and Nationalist government came into power and the system of apartheid began to emerge from their legislation," Fugard replied, "they piled one evil brick on top of another. Important choices had to be made. They targeted those of us -- intellectuals and artists -- who found ourselves the dissident voices within the society. At that point in time, the early 80s, violent resistance to apartheid had not yet started. Even though I was always a loner and never committed myself to a political party, I was harassed with midnight searches, heard that my play had been banned, or discovered that my telephone had been tapped. Others who were more politically committed were subjected to house arrests and detentions without trials, and in many cases torture."

"Many of my writer friends became artistically impotent once they had been silenced in that way," continued Fugard. "What kind of a contribution to the struggle is that: to sit in your comfortable white suburban home watching [quoting from the play] 'the world around you go up in flames.' A lot of them made the choice to leave the country with a one-way exit permit (an alternative that the government offered). It was a way for the government to purge the society of troublesome elements. In exile, they dried up creatively. Two of my friends went on to commit suicide. I am writing from something I witnessed.

"As with most things I graft aspects of myself onto one if not all of the characters. In the case of David, there are aspects of myself, that passionate love of the Karoo, that passionate sense of being an Afrikaner. And the title tells exactly what my play is about. It comes from Ovid's Latin book of poems, "Sorrows," that he wrote during exile. It is both a sorrowing for the pain of my country and the Rejoicings of what it is becoming. Even in the darkest years of apartheid, I could never hand myself over to total despair. The people, particularly the real victims, the black, the brown, the Indians, were inspirational. With all that the government tried, they never broke the spirit of the people. I hope that audiences will see a celebration of life in each of the characters in the play. In my play, the last memory Marta has of David is of this young poet in full flight who has just created a poem by putting together the names of the dispossessed colored people. The amazing thing is that the house, just like what has happened in my country, now belongs to Rebecca, who must decide whether to stay and maintain it or sell it."

Added Fugard, "Selling out to corruption is the challenge that South Africa faces now. It is frightening and bewildering the degree of corruption that is there at the moment. It is, in a sense, a betrayal of our struggle to free the country and make it the kind of fledgling democracy that it is. But people know that what we have won and achieved, and in Rebecca's case the house, has to be looked after. You don't throw away the best of the past. If you can rescue the good from the past, use it to help build the future."

Asked if he felt he'd eventually exhaust the issues of apartheid in his works, Fugard replied, "I thought I had until this play came along. After we had our elections, I wrote my play about transition Valley Song. Then I thought my writing was going to start a journey into myself, become more introspective, as with The Captain's Tiger. Out of left field, the play we are doing now just hit me, because I was already involved in writing another play that was very personal to me. This may surprise you, but it was about the 12th century German saint, mystic and composer Hildegard of Bingen. I already had the first draft of that play that Emily (Mann) was set to produce. But then, wham, all those images were in my head of my friends, now martyrs, who went into exile and died. They were now suddenly there as 'Sorrows and Rejoicings' with the support of Emily Mann. Because Emily is a fellow playwright, she has an understanding of the dilemma of the writer with his play. I just go along minding my own business and suddenly these plays find me. I'm not an angry man anymore, although I don't claim to be a wise old man."

"My work over the years has become sparer, simpler," noted Fugard. "My early plays were all full of the excesses of a young writer. Now I have a much more controlled use of language, although I still can't resist having my arias at times. Every character in Sorrows and Rejoicings has a chance to hold the stage with an aria."

In the move back from the personal to the political, Fugard is able to see both the positive and negative after-effects of the new South Africa. "Yes, there is a debit side," concedes the playwright. "But on the credit side is the way young South Africans of all colors are coming together to make the vision a living reality. There are some old diehards from the past who refuse to recognize that the world has changed. There is a lot of anger and resentment left over from the years of apartheid... The murders of farmers [currently in the news] have more to do with social economic causes and not motivated by race. Due to the high crime rate, we have not had money flowing into the country in terms of investment to generate jobs to feed the people. Poverty in the new South Africa, housing, and unemployment is as big a problem as it was in the old South Africa. The economy is really just limping along. And then, when the president makes a stupid remark that HIV doesn't cause AIDS, it makes South Africa look like it's not marching forward but stepping backward. He has now swallowed his words and said he won't speak on the subject anymore, thank God, and the government is now acknowledging a way to deal with the problem. We are locked right now in a very important court battle between the government and the drug companies. We cannot afford to pay the prices that the drug companies are charging. We want to import generics made in other countries, but are told that it would be violating copyrights."

Fugard makes it clear there's still room -- and reason -- for politically aware theater dealing with his homeland. "In South Africa, a lot of people want to run away from anything that resembles reality, to just sit back and watch Noel Coward," said Fugard. "Theater is one of the ways in which society deals with its pain, its conscience. Theater and all the arts, however, played a major role in the fight against apartheid."

Gone are the days when this "harmless old liberal fossil" will see a play of his yanked off the stage in Durban, or have his passport withdrawn. Currently a resident of southern California, Fugard, says he feels very much at "home" at McCarter, his home away from home. He concludes: "On the threshold of my 70th year, here I am with a new play coming together in a rehearsal room. Oh, my gosh, I never thought I'd get this far." It's apparent that Fugard has only just begun the next leg of his artistic journey, one that he himself has called "the start of a regenerative process." How wonderful it is for people the world over to be a part of this journey.

[END]