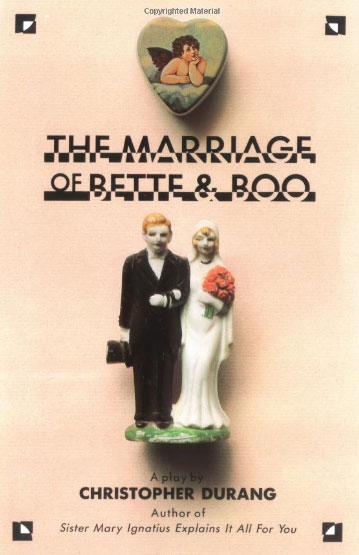

Christopher Durang's The Marriage of Bette and Boo was first produced by the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1985. It was revived Off-Broadway in 2008. Likewise, Milwaukee's Boulevard Theater first explored this dark comedy a decade ago; it, too, is staging a revival.

In a way, this theater company and the play are a perfect match. First, the Boulevard's staging is untraditional. Part of this is due to the postcard-sized stage that prohibits oversized sets, elaborate props or even complex dance moves. Size restrictions (and miniscule budgets) translate to scaling down everything to its essence. Durang's play is a nice fit because it, too, is untraditional and focuses on the essence of a family's existence. In the play, characters appear in more than 30 brief scenes. The audience learns about them bit by bit as the play progresses.

The play centers on a young married couple, Bette and Boo. It opens on their wedding day. In the span of the next 20 years, the play takes a "snapshot" of some of their family gatherings. Bette, the main character, is a simple-minded girl who longs only to have a large family and a happy marriage. Unfortunately, she has neither. Boo, a clueless dope and alcoholic, is not the model husband Bette wants him to be. So she becomes a nag.

Their first attempt at parenthood is successful. They are overjoyed at the birth of their son, Matthew. Bette nicknames him "Skippy," after her favorite character in a film. "Skippy" is the play's narrator, who sometimes appears in the scenes and sometimes merely comments from the wings. He is a substitute for Durang in this semi-autobiographical play. The entire play is seen through Skippy's eyes, which may account for the choppy nature of some scenes. Sadly, Skippy remains an only child as Bette's subsequent babies are stillborn. Each time, a doctor announces the outcome by entering the waiting room with the child in his arms. He drops the baby on the floor, saying, "it's dead." He quickly disappears. For some reason, this absurd behavior strikes the audience as funny which of course, it is definitely not.

The play is a delicate balance of comedy and tragedy, thanks to the direction of Mark Bucher, the company's artistic director. One of the play's most memorable scenes is the Thanksgiving when Skippy was ten. Boo is drinking in the basement, and Bette is yelling at him to come upstairs before the company arrives. An unattended turkey is burning in the oven. Relatives arrive, bringing dishes for this potluck affair. When gravy accidentally spills on a section of the carpet, Boo tries to clean up the mess with a vacuum cleaner. This puts Bette over the edge and the relatives make a quick exit as tempers escalate. Skippy disappears to the kitchen, returning with a bucket of warm, soapy water and sponges. Bette helps Boo extract the gravy from the carpet, barely noticing that their company has escaped. This is one of the few "normal" episodes in a play that ranges from the ordinary to the bizarre, often in the same scene.

As Bette, Anne Miller maintains her optimistic outlook despite the disappointments that life brings. A devout Catholic, she turns to the church for solutions to her problems. Durang, author of Sister Mary Ignatius Explains it All for You, doesn't miss an opportunity to excoriate the church. One of the funniest characters is Father Donnally (David Flores). He has more quips and one-liners than Don Rickles as he attempts to give Bette marital advice. Father Donnally is so out of touch that he lies on the floor, imitating frying bacon, as he tries to make a point about maintaining marital unity.

The rest of the cast also perform admirably. Particular mention must be made of the two mothers, Michelle Waide (Bette's mother) and Christine Horgen (Boo's mother). These women soldier on despite many of life's unanticipated drawbacks.

In some ways, The Marriage of Bette and Boo is a reality check for those of us who expect the holidays to be one long Hallmark moment. Durang's message is that life's moments good and bad -- are merely a series of experiences. Their real "meaning" may never be comprehended; thus, like Skippy, one can only come to a point of acceptance. That's a pretty heavy message to absorb during the holidays, but the Boulevard does an excellent job of presenting Durang's viewpoint.